The GLIMMIX Procedure

-

Overview

-

Getting Started

-

Syntax

PROC GLIMMIX StatementBY StatementCLASS StatementCODE StatementCONTRAST StatementCOVTEST StatementEFFECT StatementESTIMATE StatementFREQ StatementID StatementLSMEANS StatementLSMESTIMATE StatementMODEL StatementNLOPTIONS StatementOUTPUT StatementPARMS StatementRANDOM StatementSLICE StatementSTORE StatementWEIGHT StatementProgramming StatementsUser-Defined Link or Variance Function

PROC GLIMMIX StatementBY StatementCLASS StatementCODE StatementCONTRAST StatementCOVTEST StatementEFFECT StatementESTIMATE StatementFREQ StatementID StatementLSMEANS StatementLSMESTIMATE StatementMODEL StatementNLOPTIONS StatementOUTPUT StatementPARMS StatementRANDOM StatementSLICE StatementSTORE StatementWEIGHT StatementProgramming StatementsUser-Defined Link or Variance Function -

Details

Generalized Linear Models TheoryGeneralized Linear Mixed Models TheoryGLM Mode or GLMM ModeStatistical Inference for Covariance ParametersDegrees of Freedom MethodsEmpirical Covariance ("Sandwich") EstimatorsExploring and Comparing Covariance MatricesProcessing by SubjectsRadial Smoothing Based on Mixed ModelsOdds and Odds Ratio EstimationParameterization of Generalized Linear Mixed ModelsResponse-Level Ordering and ReferencingComparing the GLIMMIX and MIXED ProceduresSingly or Doubly Iterative FittingDefault Estimation TechniquesDefault OutputNotes on Output StatisticsODS Table NamesODS Graphics

Generalized Linear Models TheoryGeneralized Linear Mixed Models TheoryGLM Mode or GLMM ModeStatistical Inference for Covariance ParametersDegrees of Freedom MethodsEmpirical Covariance ("Sandwich") EstimatorsExploring and Comparing Covariance MatricesProcessing by SubjectsRadial Smoothing Based on Mixed ModelsOdds and Odds Ratio EstimationParameterization of Generalized Linear Mixed ModelsResponse-Level Ordering and ReferencingComparing the GLIMMIX and MIXED ProceduresSingly or Doubly Iterative FittingDefault Estimation TechniquesDefault OutputNotes on Output StatisticsODS Table NamesODS Graphics -

Examples

Binomial Counts in Randomized BlocksMating Experiment with Crossed Random EffectsSmoothing Disease Rates; Standardized Mortality RatiosQuasi-likelihood Estimation for Proportions with Unknown DistributionJoint Modeling of Binary and Count DataRadial Smoothing of Repeated Measures DataIsotonic Contrasts for Ordered AlternativesAdjusted Covariance Matrices of Fixed EffectsTesting Equality of Covariance and Correlation MatricesMultiple Trends Correspond to Multiple Extrema in Profile LikelihoodsMaximum Likelihood in Proportional Odds Model with Random EffectsFitting a Marginal (GEE-Type) ModelResponse Surface Comparisons with Multiplicity AdjustmentsGeneralized Poisson Mixed Model for Overdispersed Count DataComparing Multiple B-SplinesDiallel Experiment with Multimember Random EffectsLinear Inference Based on Summary DataWeighted Multilevel Model for Survey DataQuadrature Method for Multilevel Model

Binomial Counts in Randomized BlocksMating Experiment with Crossed Random EffectsSmoothing Disease Rates; Standardized Mortality RatiosQuasi-likelihood Estimation for Proportions with Unknown DistributionJoint Modeling of Binary and Count DataRadial Smoothing of Repeated Measures DataIsotonic Contrasts for Ordered AlternativesAdjusted Covariance Matrices of Fixed EffectsTesting Equality of Covariance and Correlation MatricesMultiple Trends Correspond to Multiple Extrema in Profile LikelihoodsMaximum Likelihood in Proportional Odds Model with Random EffectsFitting a Marginal (GEE-Type) ModelResponse Surface Comparisons with Multiplicity AdjustmentsGeneralized Poisson Mixed Model for Overdispersed Count DataComparing Multiple B-SplinesDiallel Experiment with Multimember Random EffectsLinear Inference Based on Summary DataWeighted Multilevel Model for Survey DataQuadrature Method for Multilevel Model - References

From Penalized Splines to Mixed Models

The connection between splines and mixed models arises from the similarity of the penalized spline fitting criterion to the

minimization problem that yields the mixed model equations and solutions for  and

and  . This connection is made explicit in the following paragraphs. An important distinction between classical spline fitting

and its mixed model smoothing variant, however, lies in the nature of the spline coefficients. Although they address similar

minimization criteria, the solutions for the spline coefficients in the GLIMMIX procedure are the solutions of random effects,

not fixed effects. Standard errors of predicted values, for example, account for this source of variation.

. This connection is made explicit in the following paragraphs. An important distinction between classical spline fitting

and its mixed model smoothing variant, however, lies in the nature of the spline coefficients. Although they address similar

minimization criteria, the solutions for the spline coefficients in the GLIMMIX procedure are the solutions of random effects,

not fixed effects. Standard errors of predicted values, for example, account for this source of variation.

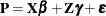

Consider the linearized mixed pseudo-model from the section The Pseudo-model,  . One derivation of the mixed model equations, whose solutions are

. One derivation of the mixed model equations, whose solutions are  and

and  , is to maximize the joint density of

, is to maximize the joint density of  with respect to

with respect to  and

and  . This is not a true likelihood problem, because

. This is not a true likelihood problem, because  is not a parameter, but a random vector.

is not a parameter, but a random vector.

In the special case with ![$\mr{Var}[\bepsilon ] = \phi \bI $](images/statug_glimmix0858.png) and

and ![$\mr{Var}[\bgamma ] = \sigma ^2 \bI $](images/statug_glimmix0859.png) , the maximization of

, the maximization of  is equivalent to the minimization of

is equivalent to the minimization of

![\[ Q(\bbeta ,\bgamma ) = \phi ^{-1}(\mb{p} - \bX \bbeta - \bZ \bgamma )’ (\mb{p} - \bX \bbeta - \bZ \bgamma ) + \sigma ^{-2} \bgamma ’\bgamma \]](images/statug_glimmix0860.png)

Now consider a linear spline as in Ruppert, Wand, and Carroll (2003, p. 108),

![\[ p_ i = \beta _0 + \beta _1 x_ i + \sum _{j=1}^{K} \gamma _ j (x_ i - t_ j)_+ \]](images/statug_glimmix0861.png)

where the  denote the spline coefficients at knots

denote the spline coefficients at knots  . The truncated line function is defined as

. The truncated line function is defined as

![\[ (x - t)_+ = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} x - t & \quad x > t \\ 0 & \quad \mr{ otherwise} \end{array} \right. \]](images/statug_glimmix0864.png)

If you collect the intercept and regressor x into the matrix  , and if you collect the truncated line functions into the

, and if you collect the truncated line functions into the  matrix

matrix  , then fitting the linear spline amounts to minimization of the penalized spline criterion

, then fitting the linear spline amounts to minimization of the penalized spline criterion

![\[ Q^*(\bbeta ,\bgamma ) = (\mb{p} - \mb{X}\bbeta - \mb{Z}\bgamma )’ (\mb{p} - \mb{X}\bbeta - \mb{Z}\bgamma ) + \lambda ^2 \bgamma ’\bgamma \]](images/statug_glimmix0865.png)

where  is the smoothing parameter.

is the smoothing parameter.

Because minimizing  with respect to

with respect to  and

and  is equivalent to minimizing

is equivalent to minimizing  , both problems lead to the same solution, and

, both problems lead to the same solution, and  is the smoothing parameter. The mixed model formulation of spline smoothing has the advantage that the smoothing parameter

is selected "automatically." It is a function of the covariance parameter estimates, which, in turn, are estimated according

to the method you specify with the METHOD=

option in the PROC GLIMMIX

statement.

is the smoothing parameter. The mixed model formulation of spline smoothing has the advantage that the smoothing parameter

is selected "automatically." It is a function of the covariance parameter estimates, which, in turn, are estimated according

to the method you specify with the METHOD=

option in the PROC GLIMMIX

statement.

To accommodate nonnormal responses and general link functions, the GLIMMIX procedure uses ![$\mr{Var}[\bepsilon ] = \phi \widetilde{\bDelta }^{-1}\mb{A}\widetilde{\bDelta }^{-1}$](images/statug_glimmix0869.png) , where

, where  is the matrix of variance functions and

is the matrix of variance functions and  is the diagonal matrix of mean derivatives defined earlier. The correspondence between spline smoothing and mixed modeling

is then one between a weighted linear mixed model and a weighted spline. In other words, the minimization criterion that yields

the estimates

is the diagonal matrix of mean derivatives defined earlier. The correspondence between spline smoothing and mixed modeling

is then one between a weighted linear mixed model and a weighted spline. In other words, the minimization criterion that yields

the estimates  and solutions

and solutions  is then

is then

![\[ Q(\bbeta ,\bgamma ) = \phi ^{-1} (\mb{p} - \mb{X}\bbeta - \mb{Z}\bgamma )’ \widetilde{\bDelta }\mb{A}^{-1}\widetilde{\bDelta } (\mb{p} - \mb{X}\bbeta - \mb{Z}\bgamma )’ + \sigma ^{-2}\bgamma ’\bgamma \]](images/statug_glimmix0871.png)

If you choose the TYPE=RSMOOTH covariance structure, PROC GLIMMIX chooses radial basis functions as the spline basis and transforms them to approximate a thin-plate spline as in Chapter 13.4 of Ruppert, Wand, and Carroll (2003). For computational expediency, the number of knots is chosen to be less than the number of data points. Ruppert, Wand, and Carroll (2003) recommend one knot per every four unique regressor values for one-dimensional smoothers. In the multivariate case, general recommendations are more difficult, because the optimal number and placement of knots depend on the spatial configuration of samples. Their recommendation for a bivariate smoother is one knot per four samples, but at least 20 and no more than 150 knots (Ruppert, Wand, and Carroll 2003, p. 257).

The magnitude of the variance component  depends on the metric of the random effects. For example, if you apply radial smoothing in time, the variance changes if

you measure time in days or minutes. If the solution for the variance component is near zero, then a rescaling of the random

effect data can help the optimization problem by moving the solution for the variance component away from the boundary of

the parameter space.

depends on the metric of the random effects. For example, if you apply radial smoothing in time, the variance changes if

you measure time in days or minutes. If the solution for the variance component is near zero, then a rescaling of the random

effect data can help the optimization problem by moving the solution for the variance component away from the boundary of

the parameter space.