Chapter Contents

Previous

Next

Chapter Contents |

Previous |

Next |

| SAS/C C++ Development System User's Guide, Release 6.50 |

The fundamental concepts of I/O in C++ are those of streams, insertion, and extraction. An input stream is a source of characters; that is, it is an object from which characters can be obtained (extracted). An output stream is a sink for characters; that is, it is an object to which characters can be directed (inserted). (It is also possible to have bidirectional streams, which can both produce and consume characters.) This section explains the basics of performing C++ I/O. For more details, refer to your C++ programming manual.

This section covers the following components of C++ I/O:

Insertion is the operation

of sending characters to a stream, expressed by the overloaded insertion operator

<<

. Thus, the following statement sends the character

'x'

to the stream

cout

:

cout << `x'; |

>>

. The following expression (where

ch

has type

char

) obtains a single character from the stream

cin

and stores it in

ch

.

cin >> ch; |

'1'

,

'2'

, and

'3'

are inserted into the stream

cout

, after which characters are

extracted from

cin

, interpreted as an integer, and the result

is assigned to

i

:

int i = 123; cout << i; cin >> i; |

class fraction

{

int numer;

unsigned denom;

friend ostream& operator <<(ostream& os,

fraction& f)

{

return os << f.numer << `/' << f.denom;

};

};

|

These statements define an insertion operator for a user-defined

fraction

class, which can be used as conveniently and easily as insertion

of characters or

ints

.

The definition of C++ stream I/O makes use of the concepts of the get pointer and the put pointer. The get pointer for a stream indicates the position in the stream from which characters are extracted. Similarly, the put pointer for a stream indicates the position in the stream where characters are inserted. Use of the insertion or extraction operator on a stream causes the appropriate pointer to move. Note that these are abstract pointers, referencing positions in the abstract sequence of characters associated with the stream, not C++ pointers addressing specific memory locations.

You can use member functions of the various stream classes to move the

get or put pointer without performing an extraction or insertion. For example,

the

fstream::seekoff()

member function moves the get and put pointers

for an

fstream

.

The exact behavior of the get and put pointers for a stream depends

on the type of stream. For example, for

fstream

objects, the get and put

pointers are tied together. That is, any operation that moves one always moves

the other. For

strstream

objects, the pointers are independent.

That is, either pointer can be moved without affecting

the other.

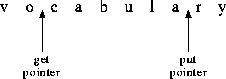

The get and put pointers reference positions between the characters of the stream, not the characters themselves. For example, consider the following sequence of characters as a stream, with the positions of the get and put pointers as marked in Illustration of Get and Put Pointers :

Illustration of Get and Put Pointers

In this example, the next character extracted from the stream is '

c

', and the next character inserted into the stream replaces the '

r

'.

This section

covers the basics of using streams, including explaining which streams are

provided by the streams library, how the different streams classes are related,

which member functions are available for use with streams, and how to create

your own streams.

The streams library provides four different kinds of streams:

strstreamfstreamstdiostreambsamstreamstdiostream

objects should be used in programs that use the C standard I/O package

as well as C++, to avoid interference between the two forms of

I/O; on some implementations,

fstreams

provide better performance

than

stdiostreams

when interaction with C I/O is not an issue.

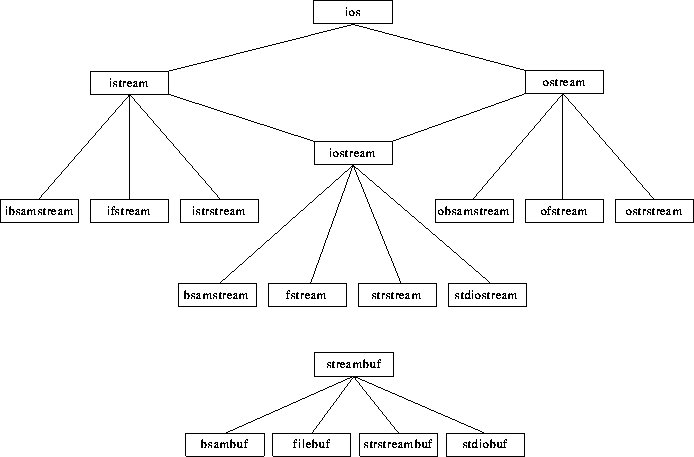

Other types of streams can be defined by derivation from the base classes

iostream

and

streambuf

. See Stream class hierarchy for more information on the relationships

between these classes.

Every C++ program begins execution with four defined streams:

To use these streams, you must include the header file

iostream.h

.

Additional streams can be created by the program as necessary. For more

in- formation, see Creating streams

.

All the

different stream classes are derived from two common base classes:

ios

and

streambuf

.

class ios

is a base class for the classes

istream

(an input stream),

ostream

(an output stream) and

iostream

(a

bidirectional stream). You are more likely to use these classes as base classes

than to use class

ios

directly. The

streambuf

class is a class that

implements buffering for streams and controls the flushing of a full output

buffer or the refilling of an empty input buffer.

Four sets of stream classes are provided in the standard streams library:

fstream

,

strstream

,

stdiostream

, and

bsamstream

. Corresponding to each of these stream classes

is a buffer class:

filebuf

,

strstreambuf

,

stdiobuf

,

and

bsambuf

, implementing a form of buffering appropriate to each stream.

Note that the stream classes are not derived

from the buffering classes; rather, a stream object has an associated buffering

object of the appropriate kind (for instance, an

fstream

object has an associated

filebuf

), which can be accessed directly if necessary using the

rdbuf()

member function. Relationship between Stream Classes

shows the inheritance relationships between the various classes.

Relationship between Stream Classes

In addition to providing the insertion and extraction operations, the stream classes define a number of other member functions that can be more convenient than using insertion and extra ction directly. All these functions are discussed in some detail in the class descriptions later in this chapter. The following list briefly describes a few of the most useful member functions.

get()

and

getline()\n

') is encountered, possibly with a limit to the number of characters

to be extracted.

The

get()

and

getline()

functions behave similarly, except that

getline()

extracts the final delimiter and

get()

does

not.

read()read()

is intended for use with binary data, whereas

get()

and

getline()

are usually more appropriate with text data.putback()write()flush()flush()

may

not cause any characters to be immediately written, depending on the characteristics

of the file.tie()cin

stream is automatically tied to

cout

, which

means that

cout

's buffer is flushed before

characters are extracted from

cin

. If, as is usually the case,

cin

and

cout

are both terminal files, this assures that

you see any buffered output messages before having to enter a response. Similarly,

the

cerr

stream is tied to

cout

, so that if an error message

is generated to

cerr

, any buffered output characters are written

first.seekg()

and

seekp()Note: Positioning of files is very different on 370 systems than on

many other systems. See 370 I/O Considerations

for some details. ![[cautend]](../common/images/cautend.gif)

tellg()

and

tellp()tellg()

and

tellp()

are

used to determine the read or write position for a stream. As with the seeking

functions, the results of these functions are system-dependent. See 370 I/O Considerations for

details.Streams are normally

created by declaring them or by use of the

new

operator. Creating an

fstream

or

stdiostream

entails opening the external file that is to be the source

or sink of characters. Creating

a

strstream

entails specifying the area of storage that will serve

as the source or sink of characters. For

fstream

, a stream constructor can

be used to create a stream associated with a particular file, similar to the

way the

fopen

function is used in C.

For instance, the following declaration creates an output

fstream

object,

dict

, associated with the CMS file named DICT DATA:

ofstream dict("cms:dict data");

|

When you

create an

fstream

(or a

stdiostream

), you must usually provide a filename

and an open mode. The open mode specifies the way in which the file is to

be accessed. For an

ifstream

, the

default open mode is

ios::in

, specifying input only; for an

ofstream

, the default open mode is

ios::out

, specifying output only.

See 370 I/O Considerations

for information on additional arguments that can be supplied

and for additional information on the form of filenames.

If you declare an

fstream

without specifying any arguments, a default

constructor is called that creates an unopened

fstream

. An unopened stream can

be opened by use of the member function

open()

, which accepts the same arguments

as the constructor.

When you

create a

strstream

, you must usually provide an area of memory and a length. Insertions

to the stream store into the area of memory; extractions return successive

characters from the area. When the array is full, no more characters can be

inserted; when all characters have been extracted,

the

ios::eof

flag is set for the stream. For an

istrstream

, the length argument to the constructor is optional; if you omit it, the

end of the storage area is determined by scanning for an end-of-string delimiter

('

\0

').

For a

strstream

that permits output, you can create a dynamic stream by

using a constructor with no arguments. In this case, memory is allocated dynamically

to hold inserted characters. When all characters have been inserted, you can

use the member function

str()

to "freeze" the stream. This prevents further

insertions into the stream

and returns the address of the area where previously inserted characters have

been stored.

When a program

inserts or extracts values other than single characters, such as integers

or floating-point data, a number of different formatting options are available.

For instance, some applications might want to have an inserted

unsigned int

transmitted in decimal, while for other applications hexadecimal might be

more appropriate. A similar issue is whether white

space should be skipped on input before storing or interpreting characters

from a stream. The member function

setf()

is provided to allow program

control of such options. For instance, the following expression sets the default

for the stream

cout

to hexadecimal, so that integral values written

to

cout

will ordinarily

be transmitted in hexadecimal:

cout.setf(ios:hex, ios:basefield) |

width()fill()precision() Use of the

setf()

,

width()

, and similar member functions

is very convenient if the same specifications are used for a large number

of inserted items. If the formatting frequently changes, it is more convenient

to use a manipulator. A manipulator is an object that can be

an operand to the << or >> operator, but which modifies the state of

the stream, rather than actually inserting or extracting any data. For instance,

the manipulators

hex

and

dec

can be used to request hexadecimal

or decimal printing of integral values. Thus, the following sequence can be

used

to write out the value of

i

in decimal and the value of

x[i]

in hexadecimal:

cout << "i = " << dec << i << ", x[i] = " << hex << x[i]; |

ws |

skips white space on input. |

flush |

flushes a stream's buffer. |

endl |

inserts a newline character and then flushes the stream's buffer. |

ends |

inserts an end-of-string character (

'\0'

). |

Associated with each stream

is a set of flags indicating the I/O state of the stream. For example, the

flag

ios::eofbit

indicates that no more characters can be extracted from

a stream, and the flag

ios::failbit

indicates that some previous request failed. The I/O

state flags can be tested by member functions; for example,

cin.eof()

tests whether more characters can be extracted from the standard input stream.

The I/O state flags can be individually manipulated by using the

clear()

member

function; for example,

cout.clear(0)

clears all the I/O state flags for the stream

cout

.

For convenience, the

!

operator and the conversion to

void*

operator allow concise testing

of a stream for any error. These operators allow you to use statements such

as the following, which writes the results of the function

nextline

to

the standard output stream until an error occurs:

while(cout) cout << nextline(); |

while(cout << nextline()); |

while(cin >> datum) process(datum); |

Chapter Contents |

Previous |

Next |

Top of Page |

Copyright © Tue Feb 10 12:11:23 EST 1998 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA. All rights reserved.