Statistical Background

Populations and Parameters

Usually, there is a clearly defined set of elements

in which you are interested. This set of elements is called the universe, and a set of values associated with

these elements is called a population of values. The statistical term population has nothing to do with people. A statistical population is a collection

of values, not a collection of people. For example, a universe is

all the students at a particular school, and there could be two populations

of interest: one of height values and one of weight values. Or, a

universe is the set of all widgets manufactured by a particular company,

while the population of values could be the length of time each widget

is used before it fails.

A population of values can be described

in terms of its cumulative distribution function, which gives the proportion of the population less than or equal

to each possible value. A discrete population can also be described

by a probability function,

which gives the proportion of the population equal to each possible

value. A continuous population can often be described by a density function, which is the derivative of

the cumulative distribution function. A density function can be approximated

by a histogram that gives the proportion of the population lying

within each of a series of intervals of values. A probability density

function is like a histogram with an infinite number of infinitely

small intervals.

In

technical literature, when the term distribution is used without qualification, it generally refers to the cumulative

distribution function. In informal writing, distribution sometimes means the density function instead. Often the word distribution is used simply to refer to an abstract

population of values rather than some concrete population. Thus,

the statistical literature refers to many types of abstract distributions,

such as normal distributions, exponential distributions, Cauchy distributions,

and so on. When a phrase such as normal distribution is used, it frequently does not matter whether the cumulative distribution

function or the density function is intended.

It might be

expedient to describe a population in terms of a few measures that

summarize interesting features of the distribution. One such measure,

computed from the population values, is called a parameter. Many different parameters can be defined

to measure different aspects of a distribution.

The most commonly

used parameter is the (arithmetic) mean. If the population contains a finite number of values, then the

population mean is computed as the sum of all the values in the population

divided by the number of elements in the population. For an infinite

population, the concept of the mean is similar but requires more complicated

mathematics.

E(x) denotes the mean of a population of values

symbolized by x, such as height,

where E stands for expected value. You can also consider expected values of derived functions of

the original values. For example, if x represents height, then  is the expected value of height squared, that is,

the mean value of the population obtained by squaring every value

in the population of heights.

is the expected value of height squared, that is,

the mean value of the population obtained by squaring every value

in the population of heights.

is the expected value of height squared, that is,

the mean value of the population obtained by squaring every value

in the population of heights.

is the expected value of height squared, that is,

the mean value of the population obtained by squaring every value

in the population of heights.

Samples and Statistics

It is often impossible to measure all

of the values in a population. A collection of measured values is

called a sample. A mathematical

function of a sample of values is called a statistic. A statistic is to a sample as a parameter is to a population.

It is customary to denote statistics by Roman letters and parameters

by Greek letters. For example, the population mean is often written

as μ, whereas the sample mean is written as  . The field of statistics is largely concerned with the study of the behavior of sample statistics.

. The field of statistics is largely concerned with the study of the behavior of sample statistics.

. The field of statistics is largely concerned with the study of the behavior of sample statistics.

. The field of statistics is largely concerned with the study of the behavior of sample statistics.

Samples

can be selected in a variety of ways. Most SAS procedures assume that

the data constitute a simple random sample, which means that the sample was selected in such a way that all

possible samples were equally likely to be selected.

Statistics from

a sample can be used to make inferences, or reasonable guesses, about

the parameters of a population. For example, if you take a random

sample of 30 students from the high school, then the mean height for

those 30 students is a reasonable guess, or estimate, of the mean height of all the students in the high school. Other

statistics, such as the standard error, can provide information about

how good an estimate is likely to be.

For any population parameter,

several statistics can estimate it. Often, however, there is one

particular statistic that is customarily used to estimate a given

parameter. For example, the sample mean is the usual estimator of

the population mean. In the case of the mean, the formulas for the

parameter and the statistic are the same. In other cases, the formula

for a parameter might be different from that of the most commonly

used estimator. The most commonly used estimator is not necessarily

the best estimator in all applications.

Measures of Location

Overview of Measures of Location

Measures of

location include the mean, the median, and the mode. These measures

describe the center of a distribution. In the definitions that follow,

notice that if the entire sample changes by adding a fixed amount

to each observation, then these measures of location are shifted by

the same fixed amount.

The Median

The population median

is the central value, lying above and below half of the population

values. The sample median is the middle value when the data are arranged

in ascending or descending order. For an even number of observations,

the midpoint between the two middle values is usually reported as

the median.

The Mode

The mode is the value

at which the density of the population is at a maximum. Some densities

have more than one local maximum (peak) and are said to be multimodal. The sample mode is the value that

occurs most often in the sample. By default, PROC UNIVARIATE reports

the lowest such value if there is a tie for the most-often-occurring

sample value. PROC UNIVARIATE lists all possible modes when you specify

the MODES option in the PROC statement. If the population is continuous,

then all sample values occur once, and the sample mode has little

use.

Percentiles

Percentiles, including quantiles, quartiles, and the

median, are useful for a detailed study of a distribution. For a set

of measurements arranged in order of magnitude, the pth percentile is the value that has p percent of the measurements below it and (100−p) percent above it. The median is the 50th percentile.

Because it might not be possible to divide your data so that you

get exactly the desired percentile, the UNIVARIATE procedure uses

a more precise definition.

Quantiles

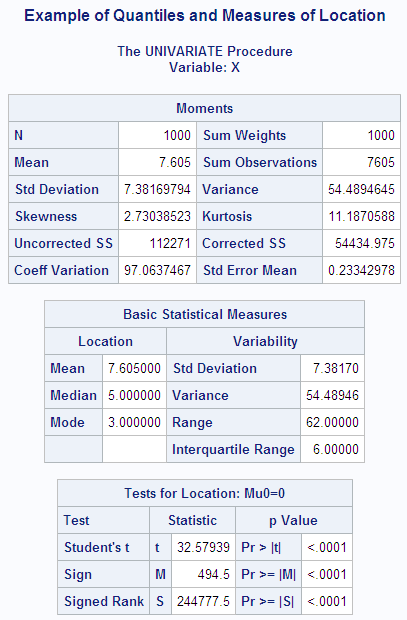

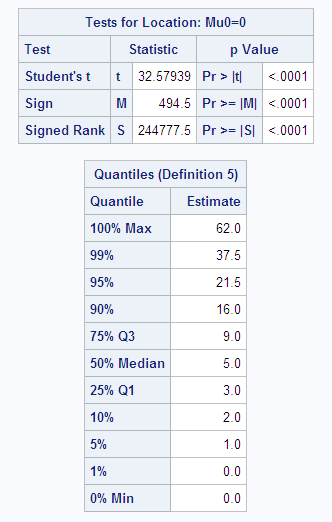

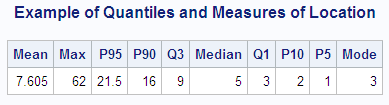

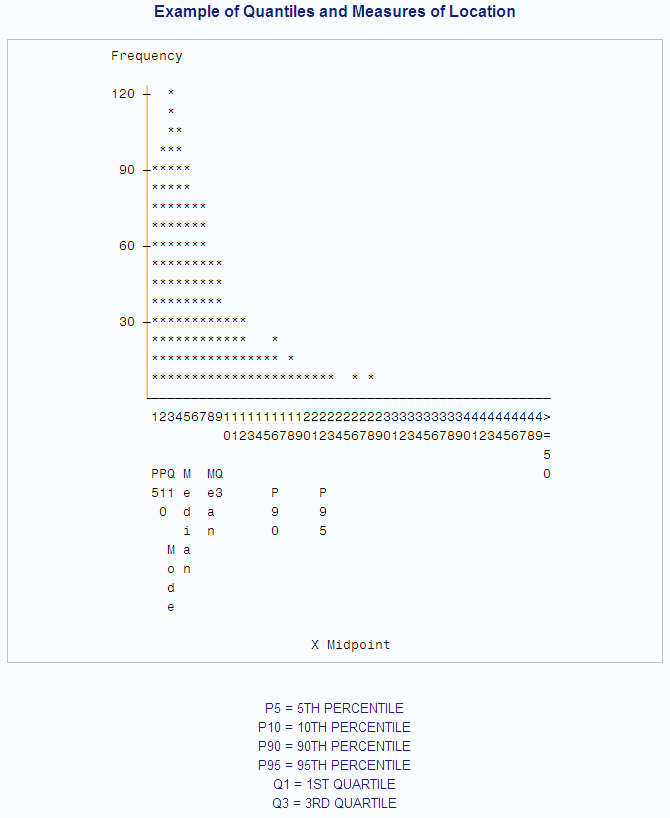

In the following example,

SAS artificially generates the data with a pseudorandom number function.

The UNIVARIATE procedure computes a variety of quantiles and measures

of location, and outputs the values to a SAS data set. A DATA step

then uses the SYMPUT routine to assign the values of the statistics

to macro variables. The macro %FORMGEN uses these macro variables

to produce value labels for the FORMAT procedure. PROC CHART uses

the resulting format to display the values of the statistics on a

histogram.

options nodate pageno=1 linesize=80 pagesize=52;

title 'Example of Quantiles and Measures of Location';

data random;

drop n;

do n=1 to 1000;

X=floor(exp(rannor(314159)*.8+1.8));

output;

end;

run;

proc univariate data=random nextrobs=0;

var x;

output out=location

mean=Mean mode=Mode median=Median

q1=Q1 q3=Q3 p5=P5 p10=P10 p90=P90 p95=P95

max=Max;

run;data _null_;

set location;

call symput('MEAN',round(mean,1));

call symput('MODE',mode);

call symput('MEDIAN',round(median,1));

call symput('Q1',round(q1,1));

call symput('Q3',round(q3,1));

call symput('P5',round(p5,1));

call symput('P10',round(p10,1));

call symput('P90',round(p90,1));

call symput('P95',round(p95,1));

call symput('MAX',min(50,max));

run;

%macro formgen;

%do i=1 %to &max;

%let value=&i;

%if &i=&p5 %then %let value=&value P5;

%if &i=&p10 %then %let value=&value P10;

%if &i=&q1 %then %let value=&value Q1;

%if &i=&mode %then %let value=&value Mode;

%if &i=&median %then %let value=&value Median;

%if &i=&mean %then %let value=&value Mean;

%if &i=&q3 %then %let value=&value Q3;

%if &i=&p90 %then %let value=&value P90;

%if &i=&p95 %then %let value=&value P95;

%if &i=&max %then %let value=>=&value;

&i="&value"

%end;

%mend;

proc format print;

value stat %formgen;

run;

options pagesize=42 linesize=80;

proc chart data=random;

vbar x / midpoints=1 to &max by 1;

format x stat.;

footnote 'P5 = 5TH PERCENTILE';

footnote2 'P10 = 10TH PERCENTILE';

footnote3 'P90 = 90TH PERCENTILE';

footnote4 'P95 = 95TH PERCENTILE';

footnote5 'Q1 = 1ST QUARTILE ';

footnote6 'Q3 = 3RD QUARTILE ';

run;Measures of Variability

Overview of Measures of Variability

Another

group of statistics is important in studying the distribution of a

population. These statistics measure the variability, also called the spread, of values. In the definitions given in

the sections that follow, notice that if the entire sample is changed

by the addition of a fixed amount to each observation, then the values

of these statistics are unchanged. If each observation in the sample

is multiplied by a constant, however, then the values of these statistics

are appropriately rescaled.

The Range

The sample range

is the difference between the largest and smallest values in the sample.

For many populations, at least in statistical theory, the range is

infinite, so the sample range might not tell you much about the population.

The sample range tends to increase as the sample size increases. If

all sample values are multiplied by a constant, then the sample range

is multiplied by the same constant.

The Variance

The population

variance, usually denoted by  , is the expected value of the squared difference

of the values from the population mean:

, is the expected value of the squared difference

of the values from the population mean:

, is the expected value of the squared difference

of the values from the population mean:

, is the expected value of the squared difference

of the values from the population mean:

The sample variance is denoted by  . The difference between a value and the mean is

called a deviation from the mean. Thus, the variance approximates the mean of the squared deviations.

. The difference between a value and the mean is

called a deviation from the mean. Thus, the variance approximates the mean of the squared deviations.

. The difference between a value and the mean is

called a deviation from the mean. Thus, the variance approximates the mean of the squared deviations.

. The difference between a value and the mean is

called a deviation from the mean. Thus, the variance approximates the mean of the squared deviations.

The Standard Deviation

The

standard deviation is the square root of the variance, or root-mean-square

deviation from the mean, in either a population or a sample. The

usual symbols are σ for the population and s for a sample. The standard deviation is expressed

in the same units as the observations, rather than in squared units.

If all sample values are multiplied by a constant, then the sample

standard deviation is multiplied by the same constant.

Coefficient of Variation

The coefficient of variation is a unitless measure of relative variability.

It is defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean expressed

as a percentage. The coefficient of variation is meaningful only if

the variable is measured on a ratio scale. If all sample values are

multiplied by a constant, then the sample coefficient of variation

remains unchanged.

Measures of Shape

Skewness

The variance is

a measure of the overall size of the deviations from the mean. Since

the formula for the variance squares the deviations, both positive

and negative deviations contribute to the variance in the same way.

In many distributions, positive deviations might tend to be larger

in magnitude than negative deviations, or vice versa. Skewness is a measure of the tendency of the

deviations to be larger in one direction than in the other. For example,

the data in the last example are skewed to the right.

Because the deviations

are cubed rather than squared, the signs of the deviations are maintained.

Cubing the deviations also emphasizes the effects of large deviations.

The formula includes a divisor of  to remove the effect of scale, so multiplying all

values by a constant does not change the skewness. Skewness can thus

be interpreted as a tendency for one tail of the population to be

heavier than the other. Skewness can be positive or negative and is

unbounded.

to remove the effect of scale, so multiplying all

values by a constant does not change the skewness. Skewness can thus

be interpreted as a tendency for one tail of the population to be

heavier than the other. Skewness can be positive or negative and is

unbounded.

to remove the effect of scale, so multiplying all

values by a constant does not change the skewness. Skewness can thus

be interpreted as a tendency for one tail of the population to be

heavier than the other. Skewness can be positive or negative and is

unbounded.

to remove the effect of scale, so multiplying all

values by a constant does not change the skewness. Skewness can thus

be interpreted as a tendency for one tail of the population to be

heavier than the other. Skewness can be positive or negative and is

unbounded.

Kurtosis

The heaviness

of the tails of a distribution affects the behavior of many statistics.

Hence it is useful to have a measure of tail heaviness. One such measure

is kurtosis. The population

kurtosis is usually defined as

Because the deviations

are raised to the fourth power, positive and negative deviations make

the same contribution, while large deviations are strongly emphasized.

Because of the divisor  , multiplying each value by a constant has no effect

on kurtosis.

, multiplying each value by a constant has no effect

on kurtosis.

, multiplying each value by a constant has no effect

on kurtosis.

, multiplying each value by a constant has no effect

on kurtosis.

Population kurtosis

must lie between  and

and  , inclusive. If

, inclusive. If  represents population skewness and

represents population skewness and  represents population kurtosis, then

represents population kurtosis, then

and

and  , inclusive. If

, inclusive. If  represents population skewness and

represents population skewness and  represents population kurtosis, then

represents population kurtosis, then

Statistical

literature sometimes reports that kurtosis measures the peakedness of a density. However, heavy tails

have much more influence on kurtosis than does the shape of the distribution

near the mean (Kaplansky 1945; Ali 1974; Johnson, et al. 1980).

Sample skewness and

kurtosis are rather unreliable estimators of the corresponding parameters

in small samples. They are better estimators when your sample is very

large. However, large values of skewness or kurtosis might merit attention

even in small samples because such values indicate that statistical

methods that are based on normality assumptions might be inappropriate.

The Normal Distribution

One

especially important family of theoretical distributions is the normal or Gaussian distribution. A normal distribution is a smooth symmetric function

often referred to as "bell-shaped." Its skewness and kurtosis are

both zero. A normal distribution can be completely specified by only

two parameters: the mean and the standard deviation. Approximately

68% of the values in a normal population are within one standard deviation

of the population mean; approximately 95% of the values are within

two standard deviations of the mean; and about 99.7% are within three

standard deviations. Use of the term normal to describe this particular type of distribution does not imply

that other types of distributions are necessarily abnormal or pathological.

Many statistical methods

are designed under the assumption that the population being sampled

is normally distributed. Nevertheless, most real-life populations

do not have normal distributions. Before using any statistical method

based on normality assumptions, you should consult the statistical

literature to find out how sensitive the method is to nonnormality

and, if necessary, check your sample for evidence of nonnormality.

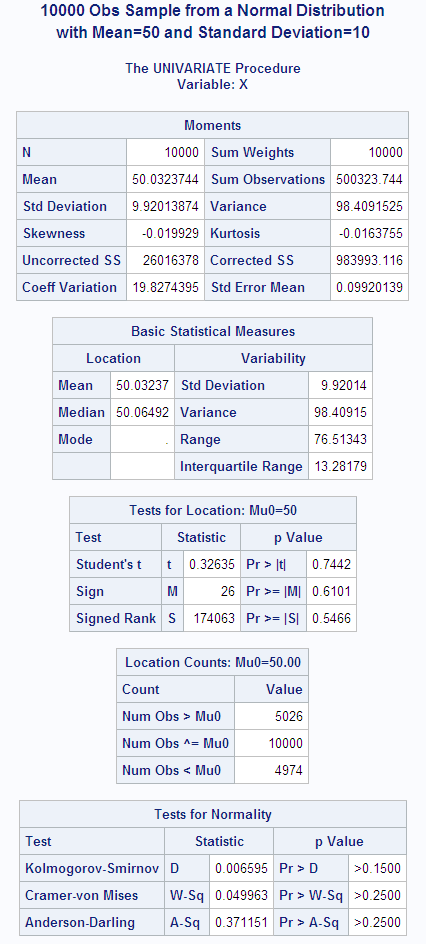

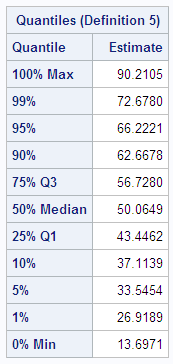

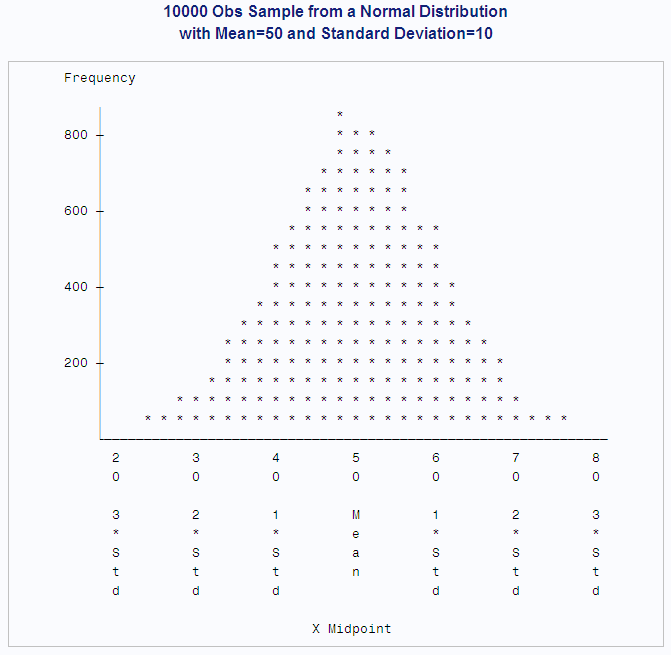

In the following example,

SAS generates a sample from a normal distribution with a mean of 50

and a standard deviation of 10. The UNIVARIATE procedure performs

tests for location and normality. Because the data are from a normal

distribution, all p-values

from the tests for normality are greater than 0.15. The CHART procedure

displays a histogram of the observations. The shape of the histogram

is a bell-like, normal density.

options nodate pageno=1 linesize=80 pagesize=52;

title '10000 Obs Sample from a Normal Distribution';

title2 'with Mean=50 and Standard Deviation=10';

data normaldat;

drop n;

do n=1 to 10000;

X=10*rannor(53124)+50;

output;

end;

run;

proc univariate data=normaldat nextrobs=0 normal

mu0=50 loccount;

var x;

run;proc format;

picture msd

20='20 3*Std' (noedit)

30='30 2*Std' (noedit)

40='40 1*Std' (noedit)

50='50 Mean ' (noedit)

60='60 1*Std' (noedit)

70='70 2*Std' (noedit)

80='80 3*Std' (noedit)

other=' ';

run;

options linesize=80 pagesize=42;

proc chart;

vbar x / midpoints=20 to 80 by 2;

format x msd.;

run;Sampling Distribution of the Mean

If you repeatedly

draw samples of size n from

a population and compute the mean of each sample, then the sample

means themselves have a distribution. Consider a new population consisting

of the means of all the samples that could possibly be drawn from

the original population. The distribution of this new population is

called a sampling distribution.

It can be proven mathematically that if the original population

has mean μ and standard deviation σ, then the sampling

distribution of the mean also has mean μ, but its standard deviation

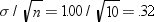

is  . The standard deviation of the sampling distribution

of the mean is called the standard error of the

mean. The standard error of the mean provides

an indication of the accuracy of a sample mean as an estimator of

the population mean.

. The standard deviation of the sampling distribution

of the mean is called the standard error of the

mean. The standard error of the mean provides

an indication of the accuracy of a sample mean as an estimator of

the population mean.

. The standard deviation of the sampling distribution

of the mean is called the standard error of the

mean. The standard error of the mean provides

an indication of the accuracy of a sample mean as an estimator of

the population mean.

. The standard deviation of the sampling distribution

of the mean is called the standard error of the

mean. The standard error of the mean provides

an indication of the accuracy of a sample mean as an estimator of

the population mean.

If the original population

has a normal distribution, then the sampling distribution of the mean

is also normal. If the original distribution is not normal but does

not have excessively long tails, then the sampling distribution of

the mean can be approximated by a normal distribution for large sample

sizes.

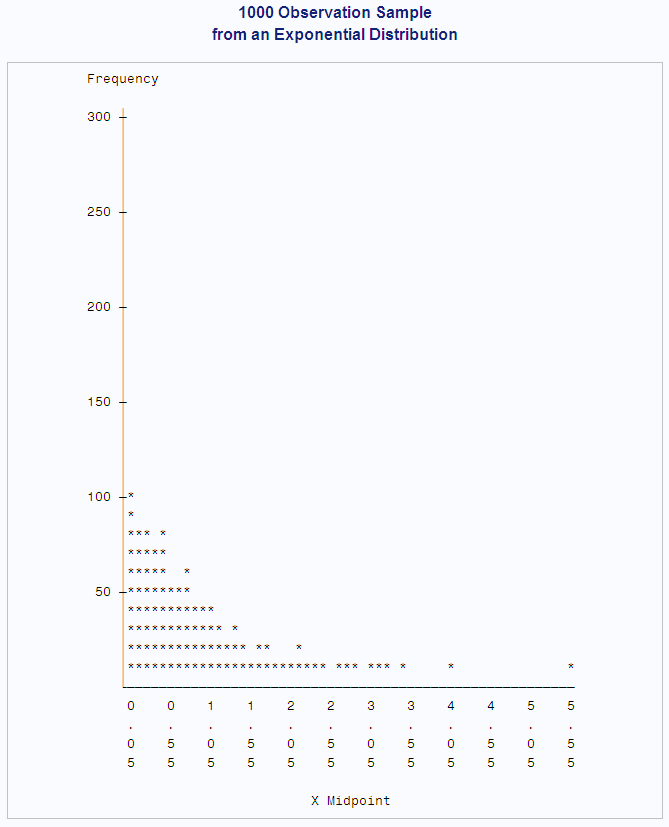

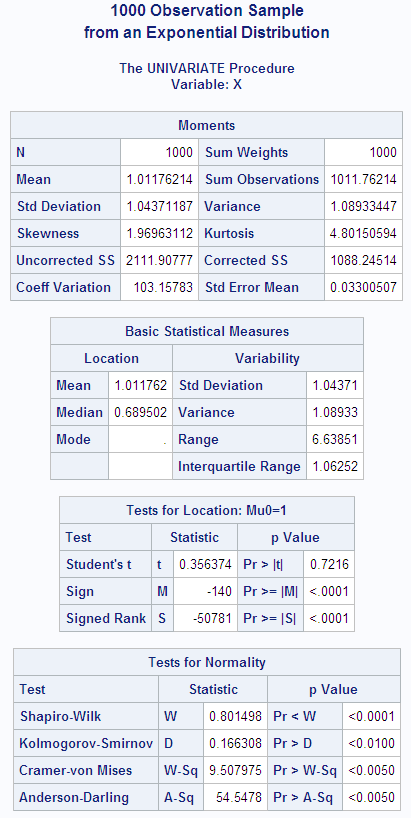

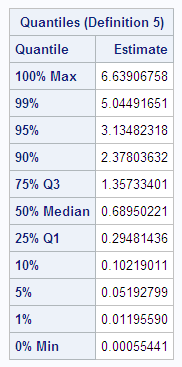

The following example

consists of three separate programs that show how the sampling distribution

of the mean can be approximated by a normal distribution as the sample

size increases. The first DATA step uses the RANEXP function to create

a sample of 1000 observations from an exponential distribution. The

theoretical population mean is 1.00, while the sample mean is 1.01,

to two decimal places. The population standard deviation is 1.00;

the sample standard deviation is 1.04.

The following example

is an example of a nonnormal distribution. The population skewness

is 2.00, which is close to the sample skewness of 1.97. The population

kurtosis is 6.00, but the sample kurtosis is only 4.80.

options nodate pageno=1 linesize=80 pagesize=42;

title '1000 Observation Sample';

title2 'from an Exponential Distribution';

data expodat;

drop n;

do n=1 to 1000;

X=ranexp(18746363);

output;

end;

run;

proc format;

value axisfmt

.05='0.05'

.55='0.55'

1.05='1.05'

1.55='1.55'

2.05='2.05'

2.55='2.55'

3.05='3.05'

3.55='3.55'

4.05='4.05'

4.55='4.55'

5.05='5.05'

5.55='5.55'

other=' ';

run;

proc chart data=expodat ;

vbar x / axis=300

midpoints=0.05 to 5.55 by .1;

format x axisfmt.;

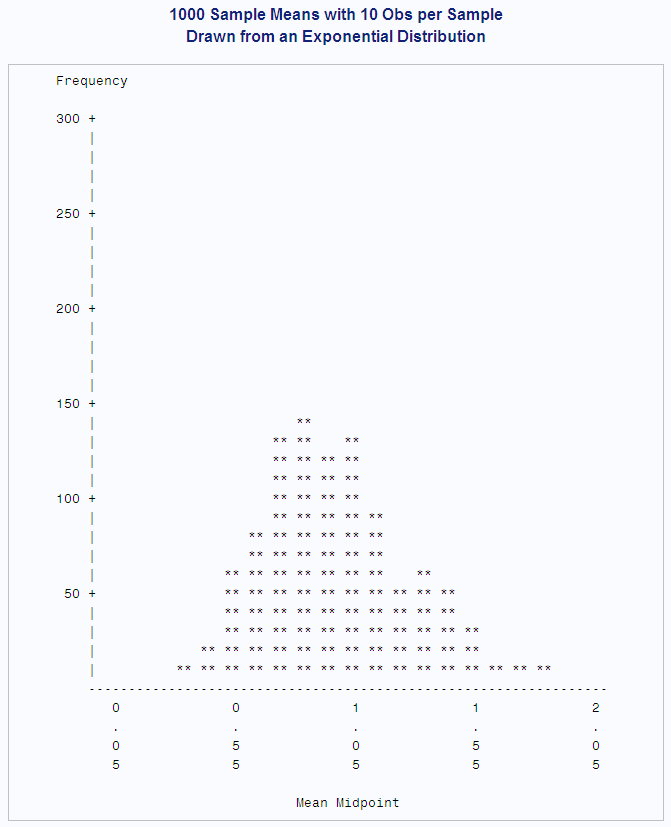

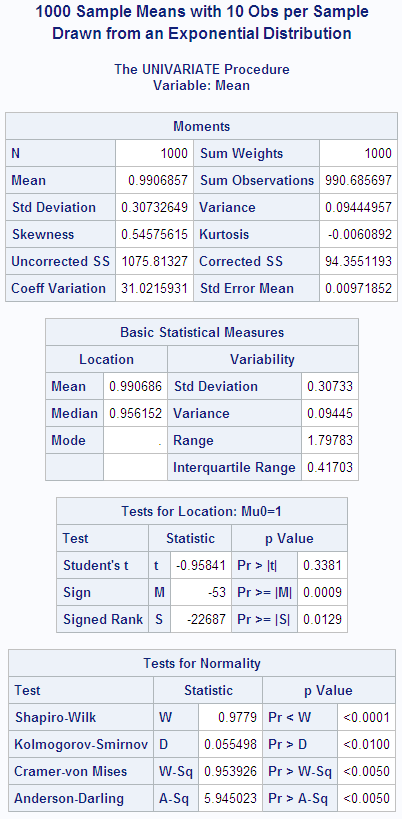

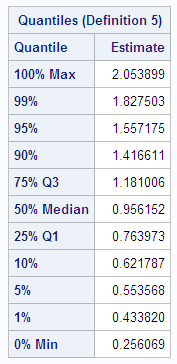

run;The next DATA step generates

1000 different samples from the same exponential distribution. Each

sample contains ten observations. The MEANS procedure computes the

mean of each sample. In the data set that is created by PROC MEANS,

each observation represents the mean of a sample of ten observations

from an exponential distribution. Thus, the data set is a sample

from the sampling distribution of the mean for an exponential population.

PROC UNIVARIATE displays

statistics for this sample of means. Notice that the mean of the sample

of means is .99, almost the same as the mean of the original population.

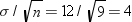

Theoretically, the standard deviation of the sampling distribution

is  , whereas the standard deviation of this sample

from the sampling distribution is .30. The skewness (.55) and kurtosis

(-.006) are closer to zero in the sample from the sampling distribution

than in the original sample from the exponential distribution because

the sampling distribution is closer to a normal distribution than

is the original exponential distribution. The CHART procedure displays

a histogram of the 1000-sample means. The shape of the histogram is

much closer to a bell-like, normal density, but it is still distinctly

lopsided.

, whereas the standard deviation of this sample

from the sampling distribution is .30. The skewness (.55) and kurtosis

(-.006) are closer to zero in the sample from the sampling distribution

than in the original sample from the exponential distribution because

the sampling distribution is closer to a normal distribution than

is the original exponential distribution. The CHART procedure displays

a histogram of the 1000-sample means. The shape of the histogram is

much closer to a bell-like, normal density, but it is still distinctly

lopsided.

, whereas the standard deviation of this sample

from the sampling distribution is .30. The skewness (.55) and kurtosis

(-.006) are closer to zero in the sample from the sampling distribution

than in the original sample from the exponential distribution because

the sampling distribution is closer to a normal distribution than

is the original exponential distribution. The CHART procedure displays

a histogram of the 1000-sample means. The shape of the histogram is

much closer to a bell-like, normal density, but it is still distinctly

lopsided.

, whereas the standard deviation of this sample

from the sampling distribution is .30. The skewness (.55) and kurtosis

(-.006) are closer to zero in the sample from the sampling distribution

than in the original sample from the exponential distribution because

the sampling distribution is closer to a normal distribution than

is the original exponential distribution. The CHART procedure displays

a histogram of the 1000-sample means. The shape of the histogram is

much closer to a bell-like, normal density, but it is still distinctly

lopsided.

options nodate pageno=1 linesize=80 pagesize=48;

title '1000 Sample Means with 10 Obs per Sample';

title2 'Drawn from an Exponential Distribution';

data samp10;

drop n;

do Sample=1 to 1000;

do n=1 to 10;

X=ranexp(433879);

output;

end;

end;

proc means data=samp10 noprint;

output out=mean10 mean=Mean;

var x;

by sample;

run;proc format;

value axisfmt

.05='0.05'

.55='0.55'

1.05='1.05'

1.55='1.55'

2.05='2.05'

other=' ';

run;

proc chart data=mean10;

vbar mean/axis=300

midpoints=0.05 to 2.05 by .1;

format mean axisfmt.;

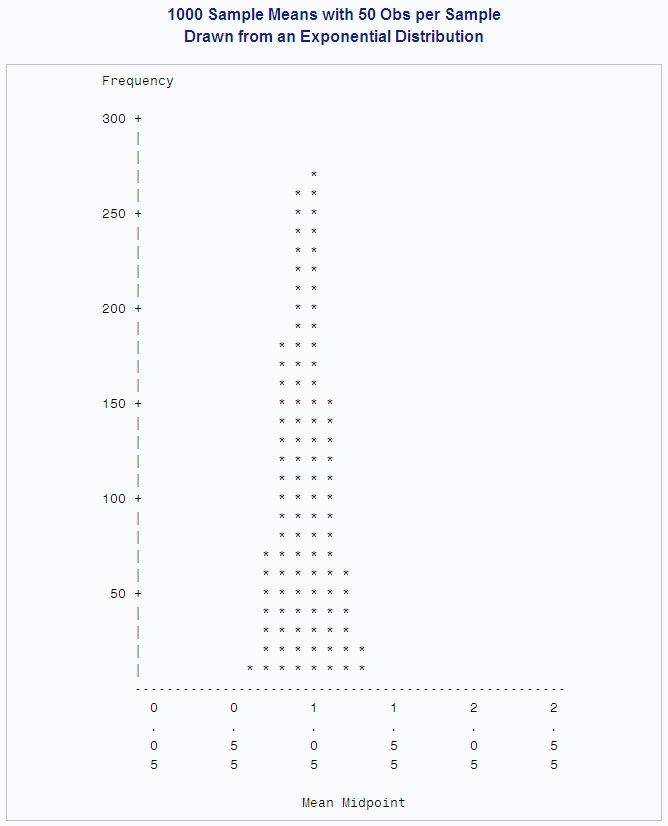

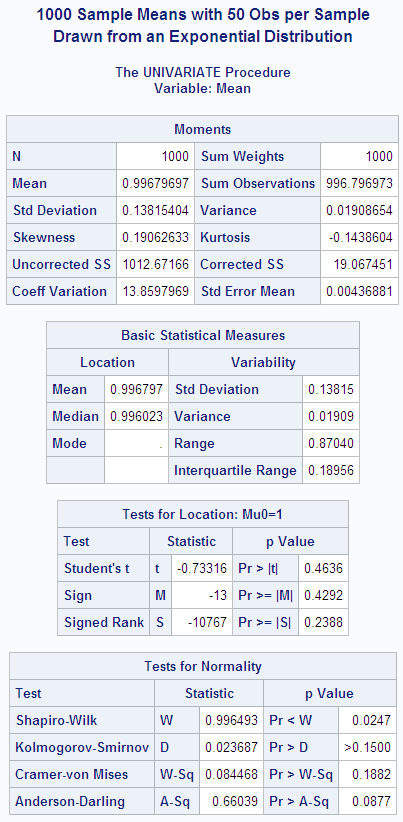

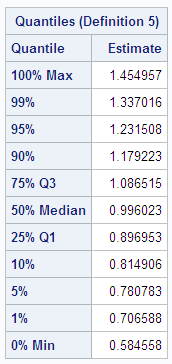

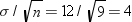

run;In the following DATA

step, the size of each sample from the exponential distribution is

increased to 50. The standard deviation of the sampling distribution

is smaller than in the previous example because the size of each sample

is larger. Also, the sampling distribution is even closer to a normal

distribution, as can be seen from the histogram and the skewness.

options nodate pageno=1 linesize=80 pagesize=48;

title '1000 Sample Means with 50 Obs per Sample';

title2 'Drawn from an Exponential Distribution';

data samp50;

drop n;

do sample=1 to 1000;

do n=1 to 50;

X=ranexp(72437213);

output;

end;

end;

proc means data=samp50 noprint;

output out=mean50 mean=Mean;

var x;

by sample;

run;Testing Hypotheses

Defining a Hypothesis

The

purpose of the statistical methods that have been discussed so far

is to estimate a population parameter by means of a sample statistic.

Another class of statistical methods is used for testing hypotheses

about population parameters or for measuring the amount of evidence

against a hypothesis.

Consider the universe

of students in a college. Let the variable X be the number of pounds

by which a student's weight deviates from the ideal weight for a person

of the same sex, height, and build. You want to find out whether

the population of students is, on the average, underweight or overweight.

To this end, you have taken a random sample of X values from nine

students, with results as given in the following DATA step:

You

can define several hypotheses of interest. One hypothesis is that,

on the average, the students are of exactly ideal weight. If μ

represents the population mean of the X values, then you can write

this hypothesis, called the null hypothesis, as  . The other two hypotheses, called alternative hypotheses, are that the students

are underweight on the average,

. The other two hypotheses, called alternative hypotheses, are that the students

are underweight on the average,  , and that the students are overweight on the average,

, and that the students are overweight on the average,

.

.

. The other two hypotheses, called alternative hypotheses, are that the students

are underweight on the average,

. The other two hypotheses, called alternative hypotheses, are that the students

are underweight on the average,  , and that the students are overweight on the average,

, and that the students are overweight on the average,

.

.

The null hypothesis

is so called because in many situations it corresponds to the assumption

of “no effect” or “no difference.” However,

this interpretation is not appropriate for all testing problems. The

null hypothesis is like a straw man that can be toppled by statistical

evidence. You decide between the alternative hypotheses according

to which way the straw man falls.

A naive way to approach

this problem would be to look at the sample mean  and decide among the three hypotheses according

to the following rule:

and decide among the three hypotheses according

to the following rule:

and decide among the three hypotheses according

to the following rule:

and decide among the three hypotheses according

to the following rule:

The trouble with this

approach is that there might be a high probability of making an incorrect

decision. If H0 is true, then you are nearly

certain to make a wrong decision because the chances of  being exactly zero are almost nil. If μ is

slightly less than zero, so that H1 is true,

then there might be nearly a 50% chance that

being exactly zero are almost nil. If μ is

slightly less than zero, so that H1 is true,

then there might be nearly a 50% chance that  will be greater than zero in repeated sampling,

so the chances of incorrectly choosing H2

would also be nearly 50%. Thus, you have a high probability of making

an error if

will be greater than zero in repeated sampling,

so the chances of incorrectly choosing H2

would also be nearly 50%. Thus, you have a high probability of making

an error if  is near zero. In such cases, there is not enough

evidence to make a confident decision, so the best response might

be to reserve judgment until you can obtain more evidence.

is near zero. In such cases, there is not enough

evidence to make a confident decision, so the best response might

be to reserve judgment until you can obtain more evidence.

being exactly zero are almost nil. If μ is

slightly less than zero, so that H1 is true,

then there might be nearly a 50% chance that

being exactly zero are almost nil. If μ is

slightly less than zero, so that H1 is true,

then there might be nearly a 50% chance that  will be greater than zero in repeated sampling,

so the chances of incorrectly choosing H2

would also be nearly 50%. Thus, you have a high probability of making

an error if

will be greater than zero in repeated sampling,

so the chances of incorrectly choosing H2

would also be nearly 50%. Thus, you have a high probability of making

an error if  is near zero. In such cases, there is not enough

evidence to make a confident decision, so the best response might

be to reserve judgment until you can obtain more evidence.

is near zero. In such cases, there is not enough

evidence to make a confident decision, so the best response might

be to reserve judgment until you can obtain more evidence.

The question is, how

far from zero must  be for you to be able to make a confident decision?

The answer can be obtained by considering the sampling distribution

of

be for you to be able to make a confident decision?

The answer can be obtained by considering the sampling distribution

of  . If X has an approximately normal distribution,

then

. If X has an approximately normal distribution,

then  has an approximately normal sampling distribution.

The mean of the sampling distribution of

has an approximately normal sampling distribution.

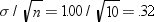

The mean of the sampling distribution of  is μ. Assume temporarily that σ, the

standard deviation of X, is known to be 12. Then the standard error

of

is μ. Assume temporarily that σ, the

standard deviation of X, is known to be 12. Then the standard error

of  for samples of nine observations is

for samples of nine observations is  .

.

be for you to be able to make a confident decision?

The answer can be obtained by considering the sampling distribution

of

be for you to be able to make a confident decision?

The answer can be obtained by considering the sampling distribution

of  . If X has an approximately normal distribution,

then

. If X has an approximately normal distribution,

then  has an approximately normal sampling distribution.

The mean of the sampling distribution of

has an approximately normal sampling distribution.

The mean of the sampling distribution of  is μ. Assume temporarily that σ, the

standard deviation of X, is known to be 12. Then the standard error

of

is μ. Assume temporarily that σ, the

standard deviation of X, is known to be 12. Then the standard error

of  for samples of nine observations is

for samples of nine observations is  .

.

You know that about

95% of the values from a normal distribution are within two standard

deviations of the mean, so about 95% of the possible samples of nine

X values have a sample mean  between

between  and

and  , or between −8 and 8. Consider the chances

of making an error with the following decision rule:

, or between −8 and 8. Consider the chances

of making an error with the following decision rule:

between

between  and

and  , or between −8 and 8. Consider the chances

of making an error with the following decision rule:

, or between −8 and 8. Consider the chances

of making an error with the following decision rule:

If H0 is true, then in about 95% of the possible samples  will be between the critical

values

will be between the critical

values  and 8, so you will reserve judgment. In these cases

the statistical evidence is not strong enough to fell the straw man.

In the other 5% of the samples you will make an error; in 2.5% of

the samples you will incorrectly choose H1,

and in 2.5% you will incorrectly choose H2.

and 8, so you will reserve judgment. In these cases

the statistical evidence is not strong enough to fell the straw man.

In the other 5% of the samples you will make an error; in 2.5% of

the samples you will incorrectly choose H1,

and in 2.5% you will incorrectly choose H2.

will be between the critical

values

will be between the critical

values  and 8, so you will reserve judgment. In these cases

the statistical evidence is not strong enough to fell the straw man.

In the other 5% of the samples you will make an error; in 2.5% of

the samples you will incorrectly choose H1,

and in 2.5% you will incorrectly choose H2.

and 8, so you will reserve judgment. In these cases

the statistical evidence is not strong enough to fell the straw man.

In the other 5% of the samples you will make an error; in 2.5% of

the samples you will incorrectly choose H1,

and in 2.5% you will incorrectly choose H2.

Significance and Power

The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis if it is true is

called the Type I error rate of the statistical test and is typically denoted as  . In this example, an

. In this example, an  value less than

value less than  or greater than 8 is said to be statistically significant at the 5% level. You

can adjust the type I error rate according to your needs by choosing

different critical values. For example, critical values of −4

and 4 would produce a significance level of about 32%, while −12

and 12 would give a type I error rate of about 0.3%.

or greater than 8 is said to be statistically significant at the 5% level. You

can adjust the type I error rate according to your needs by choosing

different critical values. For example, critical values of −4

and 4 would produce a significance level of about 32%, while −12

and 12 would give a type I error rate of about 0.3%.

. In this example, an

. In this example, an  value less than

value less than  or greater than 8 is said to be statistically significant at the 5% level. You

can adjust the type I error rate according to your needs by choosing

different critical values. For example, critical values of −4

and 4 would produce a significance level of about 32%, while −12

and 12 would give a type I error rate of about 0.3%.

or greater than 8 is said to be statistically significant at the 5% level. You

can adjust the type I error rate according to your needs by choosing

different critical values. For example, critical values of −4

and 4 would produce a significance level of about 32%, while −12

and 12 would give a type I error rate of about 0.3%.

The decision

rule is a two-tailed test

because the alternative hypotheses allow for population means either

smaller or larger than the value specified in the null hypothesis.

If you were interested only in the possibility of the students being

overweight on the average, then you could use a one-tailed test:

The probability of rejecting the null hypothesis if it is false

is called the power of the

statistical test and is typically denoted as  .

.  is called the Type II error

rate, which is the probability of not rejecting

a false null hypothesis. The power depends on the true value of the

parameter. In the example, assume that the population mean is 4. The

power for detecting H2 is the probability of

getting a sample mean greater than 8. The critical value 8 is one

standard error higher than the population mean 4. The chance of getting

a value at least one standard deviation greater than the mean from

a normal distribution is about 16%, so the power for detecting the

alternative hypothesis H2 is about 16%. If

the population mean were 8, then the power for H2 would be 50%, whereas a population mean of 12 would yield a power

of about 84%.

is called the Type II error

rate, which is the probability of not rejecting

a false null hypothesis. The power depends on the true value of the

parameter. In the example, assume that the population mean is 4. The

power for detecting H2 is the probability of

getting a sample mean greater than 8. The critical value 8 is one

standard error higher than the population mean 4. The chance of getting

a value at least one standard deviation greater than the mean from

a normal distribution is about 16%, so the power for detecting the

alternative hypothesis H2 is about 16%. If

the population mean were 8, then the power for H2 would be 50%, whereas a population mean of 12 would yield a power

of about 84%.

.

.  is called the Type II error

rate, which is the probability of not rejecting

a false null hypothesis. The power depends on the true value of the

parameter. In the example, assume that the population mean is 4. The

power for detecting H2 is the probability of

getting a sample mean greater than 8. The critical value 8 is one

standard error higher than the population mean 4. The chance of getting

a value at least one standard deviation greater than the mean from

a normal distribution is about 16%, so the power for detecting the

alternative hypothesis H2 is about 16%. If

the population mean were 8, then the power for H2 would be 50%, whereas a population mean of 12 would yield a power

of about 84%.

is called the Type II error

rate, which is the probability of not rejecting

a false null hypothesis. The power depends on the true value of the

parameter. In the example, assume that the population mean is 4. The

power for detecting H2 is the probability of

getting a sample mean greater than 8. The critical value 8 is one

standard error higher than the population mean 4. The chance of getting

a value at least one standard deviation greater than the mean from

a normal distribution is about 16%, so the power for detecting the

alternative hypothesis H2 is about 16%. If

the population mean were 8, then the power for H2 would be 50%, whereas a population mean of 12 would yield a power

of about 84%.

Student's t Distribution

In practice, you usually cannot use any decision rule that uses

a critical value based on σ because you do not usually know

the value of σ. You can, however, use s as an estimate of σ. Consider the following statistic:

This t statistic is the difference between the sample

mean and the hypothesized mean  divided by the estimated standard error of the

mean.

divided by the estimated standard error of the

mean.

divided by the estimated standard error of the

mean.

divided by the estimated standard error of the

mean.

If the null hypothesis

is true and the population is normally distributed, then the t statistic has what is called a Student's t distribution with  degrees of freedom. This distribution looks very

similar to a normal distribution, but the tails of the Student's t distribution are heavier. As the sample size

gets larger, the sample standard deviation becomes a better estimator

of the population standard deviation, and the t distribution gets closer to a normal distribution.

degrees of freedom. This distribution looks very

similar to a normal distribution, but the tails of the Student's t distribution are heavier. As the sample size

gets larger, the sample standard deviation becomes a better estimator

of the population standard deviation, and the t distribution gets closer to a normal distribution.

degrees of freedom. This distribution looks very

similar to a normal distribution, but the tails of the Student's t distribution are heavier. As the sample size

gets larger, the sample standard deviation becomes a better estimator

of the population standard deviation, and the t distribution gets closer to a normal distribution.

degrees of freedom. This distribution looks very

similar to a normal distribution, but the tails of the Student's t distribution are heavier. As the sample size

gets larger, the sample standard deviation becomes a better estimator

of the population standard deviation, and the t distribution gets closer to a normal distribution.

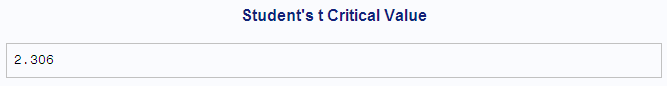

The value 2.3 was obtained

from a table of Student's t distribution to give a type I error rate of 5% for 8 (that is,  ) degrees of freedom. Most common statistics texts

contain a table of Student's t distribution. If you do not have a statistics text handy, then you

can use the DATA step and the TINV function to print any values from

the t distribution.

) degrees of freedom. Most common statistics texts

contain a table of Student's t distribution. If you do not have a statistics text handy, then you

can use the DATA step and the TINV function to print any values from

the t distribution.

) degrees of freedom. Most common statistics texts

contain a table of Student's t distribution. If you do not have a statistics text handy, then you

can use the DATA step and the TINV function to print any values from

the t distribution.

) degrees of freedom. Most common statistics texts

contain a table of Student's t distribution. If you do not have a statistics text handy, then you

can use the DATA step and the TINV function to print any values from

the t distribution.

By default, PROC UNIVARIATE

computes a t statistic for

the null hypothesis that  , along with related statistics. Use the MU0= option

in the PROC statement to specify another value for the null hypothesis.

, along with related statistics. Use the MU0= option

in the PROC statement to specify another value for the null hypothesis.

, along with related statistics. Use the MU0= option

in the PROC statement to specify another value for the null hypothesis.

, along with related statistics. Use the MU0= option

in the PROC statement to specify another value for the null hypothesis.

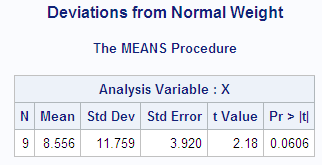

This example uses the

data on deviations from normal weight, which consist of nine observations.

First, PROC MEANS computes the t statistic for the null hypothesis that  . Then, the TINV function in a DATA step computes

the value of Student's t distribution

for a two-tailed test at the 5% level of significance and eight degrees

of freedom.

. Then, the TINV function in a DATA step computes

the value of Student's t distribution

for a two-tailed test at the 5% level of significance and eight degrees

of freedom.

. Then, the TINV function in a DATA step computes

the value of Student's t distribution

for a two-tailed test at the 5% level of significance and eight degrees

of freedom.

. Then, the TINV function in a DATA step computes

the value of Student's t distribution

for a two-tailed test at the 5% level of significance and eight degrees

of freedom.

data devnorm;

title 'Deviations from Normal Weight';

input X @@;

datalines;

-7 -2 1 3 6 10 15 21 30

;

proc means data=devnorm maxdec=3 n mean

std stderr t probt;

run;

title 'Student''s t Critical Value';

data _null_;

file print;

t=tinv(.975,8);

put t 5.3;

run;

Deviations from Normal Weight 1

The MEANS Procedure

Analysis Variable : X

N Mean Std Dev Std Error t Value Pr > |t|

--------------------------------------------------------------

9 8.556 11.759 3.920 2.18 0.0606

--------------------------------------------------------------

Student's t Critical Value 2

2.306

In the current example,

the value of the t statistic

is 2.18, which is less than the critical t value of 2.3 (for a 5% significance level and eight degrees of freedom).

Thus, at a 5% significance level you must reserve judgment. If you

had elected to use a 10% significance level, then the critical value

of the t distribution would

have been 1.86 and you could have rejected the null hypothesis. The

sample size is so small, however, that the validity of your conclusion

depends strongly on how close the distribution of the population is

to a normal distribution.

Probability Values

Another way to

report the results of a statistical test is to compute a probability value or p-value. A p-value gives the probability

in repeated sampling of obtaining a statistic as far in the directions

specified by the alternative hypothesis as is the value actually observed.

A two-tailed p-value for a t statistic is the probability of obtaining an

absolute t value that is greater

than the observed absolute t value. A one-tailed p-value

for a t statistic for the alternative

hypothesis  is the probability of obtaining a t value greater than the observed t value. Once the p-value is computed, you can perform a hypothesis test by comparing

the p-value with the desired

significance level. If the p-value is less than or equal to the type I error rate of the test,

then the null hypothesis can be rejected. The two-tailed p-value, labeled

is the probability of obtaining a t value greater than the observed t value. Once the p-value is computed, you can perform a hypothesis test by comparing

the p-value with the desired

significance level. If the p-value is less than or equal to the type I error rate of the test,

then the null hypothesis can be rejected. The two-tailed p-value, labeled

is the probability of obtaining a t value greater than the observed t value. Once the p-value is computed, you can perform a hypothesis test by comparing

the p-value with the desired

significance level. If the p-value is less than or equal to the type I error rate of the test,

then the null hypothesis can be rejected. The two-tailed p-value, labeled

is the probability of obtaining a t value greater than the observed t value. Once the p-value is computed, you can perform a hypothesis test by comparing

the p-value with the desired

significance level. If the p-value is less than or equal to the type I error rate of the test,

then the null hypothesis can be rejected. The two-tailed p-value, labeled Pr > |t| in the PROC MEANS output, is .0606, so the null hypothesis could

be rejected at the 10% significance level but not at the 5% level.