Test of Hypotheses

Consider a general linear hypothesis of the form  , where

, where  is a

is a  matrix. It is assumed that

matrix. It is assumed that  is such that this hypothesis is linearly consistent—that is, that there exists some

is such that this hypothesis is linearly consistent—that is, that there exists some  for which

for which  . This is always the case if

. This is always the case if  is in the column space of

is in the column space of  , if

, if  has full row rank, or if

has full row rank, or if  ; the latter is the most common case. Since many linear models have a rank-deficient

; the latter is the most common case. Since many linear models have a rank-deficient  matrix, the question arises whether the hypothesis is testable. The idea of testability of a hypothesis is—not surprisingly—connected to the concept of estimability as introduced previously. The hypothesis

matrix, the question arises whether the hypothesis is testable. The idea of testability of a hypothesis is—not surprisingly—connected to the concept of estimability as introduced previously. The hypothesis  is testable if it consists of estimable functions.

is testable if it consists of estimable functions.

There are two important approaches to testing hypotheses in statistical applications—the reduction principle and the linear inference approach. The reduction principle states that the validity of the hypothesis can be inferred by comparing a suitably chosen summary statistic between the model at hand and a reduced model in which the constraint  is imposed. The linear inference approach relies on the fact that

is imposed. The linear inference approach relies on the fact that  is an estimator of

is an estimator of  and its stochastic properties are known, at least approximately. A test statistic can then be formed using

and its stochastic properties are known, at least approximately. A test statistic can then be formed using  , and its behavior under the restriction

, and its behavior under the restriction  can be ascertained.

can be ascertained.

The two principles lead to identical results in certain—for example, least squares estimation in the classical linear model. In more complex situations the two approaches lead to similar but not identical results. This is the case, for example, when weights or unequal variances are involved, or when  is a nonlinear estimator.

is a nonlinear estimator.

Reduction Tests

The two main reduction principles are the sum of squares reduction test and the likelihood ratio test. The test statistic in the former is proportional to the difference of the residual sum of squares between the reduced model and the full model. The test statistic in the likelihood ratio test is proportional to the difference of the log likelihoods between the full and reduced models. To fix these ideas, suppose that you are fitting the model  , where

, where  . Suppose that

. Suppose that  denotes the residual sum of squares in this model and that

denotes the residual sum of squares in this model and that  is the residual sum of squares in the model for which

is the residual sum of squares in the model for which  holds. Then under the hypothesis the ratio

holds. Then under the hypothesis the ratio

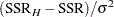

|

follows a chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the rank of  . Maybe surprisingly, the residual sum of squares in the full model is distributed independently of this quantity, so that under the hypothesis,

. Maybe surprisingly, the residual sum of squares in the full model is distributed independently of this quantity, so that under the hypothesis,

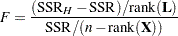

|

follows an  distribution with

distribution with  numerator and

numerator and  denominator degrees of freedom. Note that the quantity in the denominator of the

denominator degrees of freedom. Note that the quantity in the denominator of the  statistic is a particular estimator of

statistic is a particular estimator of  —namely, the unbiased moment-based estimator that is customarily associated with least squares estimation. It is also the restricted maximum likelihood estimator of

—namely, the unbiased moment-based estimator that is customarily associated with least squares estimation. It is also the restricted maximum likelihood estimator of  if

if  is normally distributed.

is normally distributed.

In the case of the likelihood ratio test, suppose that  denotes the log likelihood evaluated at the ML estimators. Also suppose that

denotes the log likelihood evaluated at the ML estimators. Also suppose that  denotes the log likelihood in the model for which

denotes the log likelihood in the model for which  holds. Then under the hypothesis the statistic

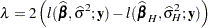

holds. Then under the hypothesis the statistic

|

follows approximately a chi-square distribution with degrees of freedom equal to the rank of  . In the case of a normally distributed response, the log-likelihood function can be profiled with respect to

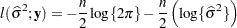

. In the case of a normally distributed response, the log-likelihood function can be profiled with respect to  . The resulting profile log likelihood is

. The resulting profile log likelihood is

|

and the likelihood ratio test statistic becomes

|

The preceding expressions show that, in the case of normally distributed data, both reduction principles lead to simple functions of the residual sums of squares in two models. As Pawitan (2001, p. 151) puts it, there is, however, an important difference not in the computations but in the statistical content. The least squares principle, where sum of squares reduction tests are widely used, does not require a distributional specification. Assumptions about the distribution of the data are added to provide a framework for confirmatory inferences, such as the testing of hypotheses. This framework stems directly from the assumption about the data’s distribution, or from the sampling distribution of the least squares estimators. The likelihood principle, on the other hand, requires a distributional specification at the outset. Inference about the parameters is implicit in the model; it is the result of further computations following the estimation of the parameters. In the least squares framework, inference about the parameters is the result of further assumptions.

Linear Inference

The principle of linear inference is to formulate a test statistic for  that builds on the linearity of the hypothesis about

that builds on the linearity of the hypothesis about  . For many models that have linear components, the estimator

. For many models that have linear components, the estimator  is also linear in

is also linear in  . It is then simple to establish the distributional properties of

. It is then simple to establish the distributional properties of  based on the distributional assumptions about

based on the distributional assumptions about  or based on large-sample arguments. For example,

or based on large-sample arguments. For example,  might be a nonlinear estimator, but it is known to asymptotically follow a normal distribution; this is the case in many nonlinear and generalized linear models.

might be a nonlinear estimator, but it is known to asymptotically follow a normal distribution; this is the case in many nonlinear and generalized linear models.

If the sampling distribution or the asymptotic distribution of  is normal, then one can easily derive quadratic forms with known distributional properties. For example, if the random vector

is normal, then one can easily derive quadratic forms with known distributional properties. For example, if the random vector  is distributed as

is distributed as  , then

, then  follows a chi-square distribution with

follows a chi-square distribution with  degrees of freedom and noncentrality parameter

degrees of freedom and noncentrality parameter  , provided that

, provided that  .

.

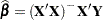

In the classical linear model, suppose that  is deficient in rank and that

is deficient in rank and that  is a solution to the normal equations. Then, if the errors are normally distributed,

is a solution to the normal equations. Then, if the errors are normally distributed,

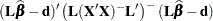

|

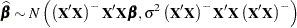

Because  is testable,

is testable,  is estimable, and thus

is estimable, and thus  , as established in the previous section. Hence,

, as established in the previous section. Hence,

|

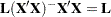

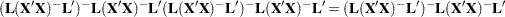

The conditions for a chi-square distribution of the quadratic form

|

are thus met, provided that

|

This condition is obviously met if  is of full rank. The condition is also met if

is of full rank. The condition is also met if  is a reflexive inverse (a

is a reflexive inverse (a  -inverse) of

-inverse) of  .

.

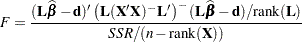

The test statistic to test the linear hypothesis  is thus

is thus

|

and it follows an  distribution with

distribution with  numerator and

numerator and  denominator degrees of freedom under the hypothesis.

denominator degrees of freedom under the hypothesis.

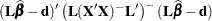

This test statistic looks very similar to the  statistic for the sum of squares reduction test. This is no accident. If the model is linear and parameters are estimated by ordinary least squares, then you can show that the quadratic form

statistic for the sum of squares reduction test. This is no accident. If the model is linear and parameters are estimated by ordinary least squares, then you can show that the quadratic form  equals the differences in the residual sum of squares,

equals the differences in the residual sum of squares,  , where

, where  is obtained as the residual sum of squares from OLS estimation in a model that satisfies

is obtained as the residual sum of squares from OLS estimation in a model that satisfies  . However, this correspondence between the two test formulations does not apply when a different estimation principle is used. For example, assume that

. However, this correspondence between the two test formulations does not apply when a different estimation principle is used. For example, assume that  and that

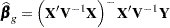

and that  is estimated by generalized least squares:

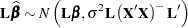

is estimated by generalized least squares:

|

The construction of  matrices associated with hypotheses in SAS/STAT software is frequently based on the properties of the

matrices associated with hypotheses in SAS/STAT software is frequently based on the properties of the  matrix, not of

matrix, not of  . In other words, the construction of the

. In other words, the construction of the  matrix is governed only by the design. A sum of squares reduction test for

matrix is governed only by the design. A sum of squares reduction test for  that uses the generalized residual sum of squares

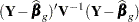

that uses the generalized residual sum of squares  is not identical to a linear hypothesis test with the statistic

is not identical to a linear hypothesis test with the statistic

|

Furthermore,  is usually unknown and must be estimated as well. The estimate for

is usually unknown and must be estimated as well. The estimate for  depends on the model, and imposing a constraint on the model would change the estimate. The asymptotic distribution of the statistic

depends on the model, and imposing a constraint on the model would change the estimate. The asymptotic distribution of the statistic  is a chi-square distribution. However, in practical applications the

is a chi-square distribution. However, in practical applications the  distribution with

distribution with  numerator and

numerator and  denominator degrees of freedom is often used because it provides a better approximation to the sampling distribution of

denominator degrees of freedom is often used because it provides a better approximation to the sampling distribution of  in finite samples. The computation of the denominator degrees of freedom

in finite samples. The computation of the denominator degrees of freedom  , however, is a matter of considerable discussion. A number of methods have been proposed and are implemented in various forms in SAS/STAT (see, for example, the degrees-of-freedom methods in the MIXED and GLIMMIX procedures).

, however, is a matter of considerable discussion. A number of methods have been proposed and are implemented in various forms in SAS/STAT (see, for example, the degrees-of-freedom methods in the MIXED and GLIMMIX procedures).